2 Military spending in Germany

Environmental impact of €100 billion in arms investments

[back to table of content]

|

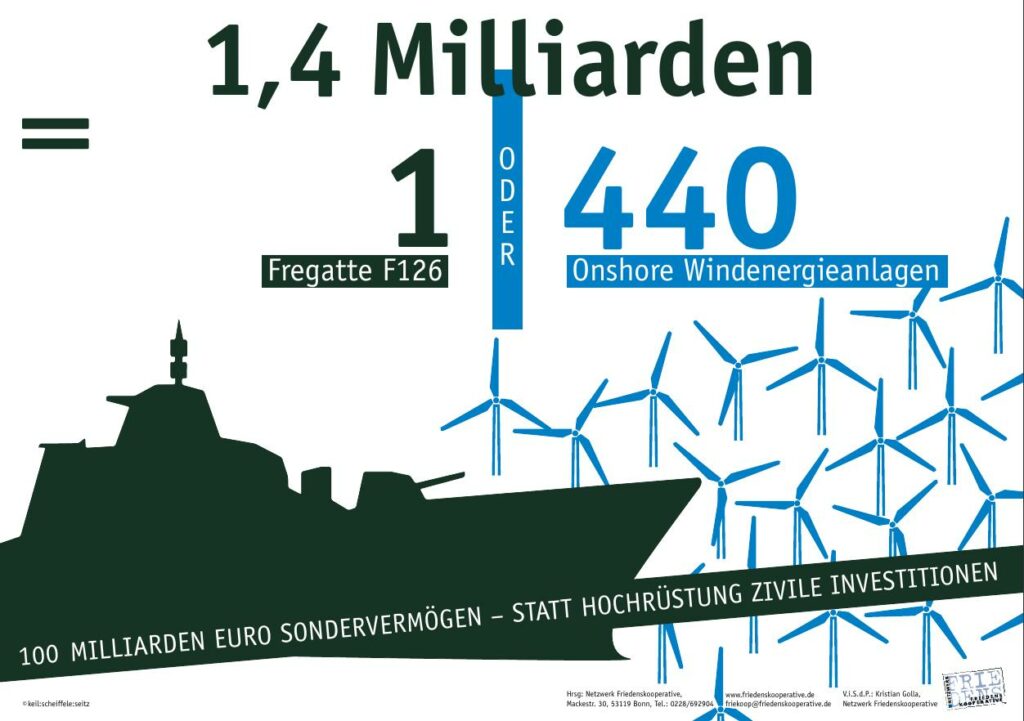

Fig. 2-1: Poster for Frigate 126 |

2.1 Budgetary expenditure for the Bundeswehr

Military expenditure in comparison

Along with the investment package, an increase in German military expenditure to two percent of GDP is envisaged, as stipulated in the corresponding legal text (see Chapter 2.2). In absolute terms, this would mean a jump of more than 20 billion euros annually, measured against the current share of 1.4% of GDP. This would put Germany ahead of Russia, i.e. in third place worldwide after the USA and China. Currently, Germany ranks 11th worldwide.2Generally, however, monetary input says only limited things about military output (whether this is measured in terms of the number of tanks, general combat value or something else) and even less about accompanying (in)security. However, the military expenditure of a year is only of limited significance, since modernisation and upgrading are mostly long-term processes; the figures of a year, on the other hand, are only a snapshot, especially in the case of procurement. If one looks at the past years, however, one finds that the picture hardly changes.3Comparative figures or graphs at Bayer u. Mutschler, March 2022

Structure of German military expenditure

German military spending has been continuously increased since 2015. Essentially, these are included in Section 144Source: https://bundeshaushalt.de of the federal budget. In the corresponding expenditures of the Federal Ministry of Defense (BMVg) 2022 amounting to 50.4 billion euros, military procurements have a share of 9.8 billion euros.5Still relevant in the present context are: Accommodation (stationary infrastructure) with 6.0 billion euros, material maintenance with 4.6 billion euros and defense research, development and testing with 2.2 billion euros.

For the share of military spending in GDP, other budget items are also added, which is why we also talk about military spending according to NATO criteria, which are relevant for the spending target proclaimed by NATO member states. This figure is about 5 billion euros higher than that of Section 14, i.e. German military spending for 2022 thus amounts to 55.6 billion euros.6See also Wagner, 2022

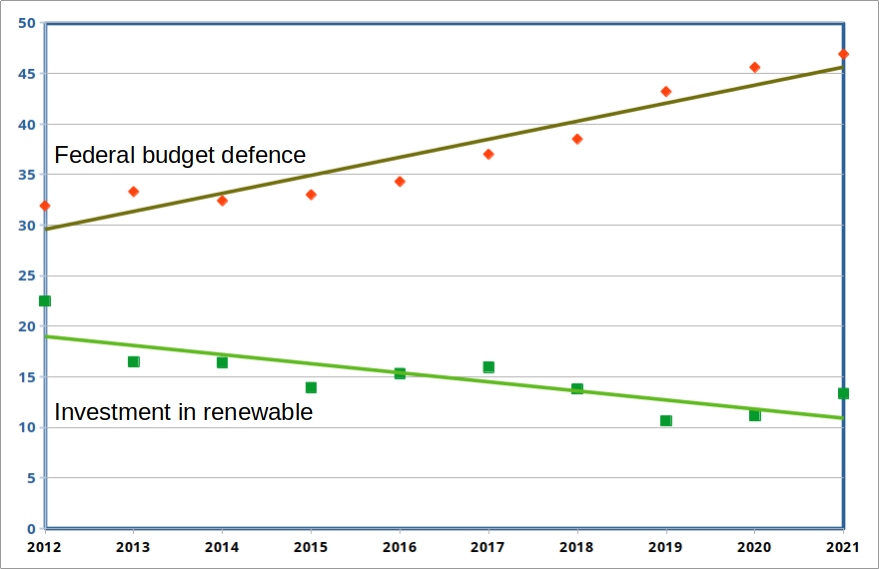

| Fig. 2-2: Development of German military expenditures and investments in renewable energies in trend lines

German defense spending has risen continuously since 2014. By way of comparison, Germany invested around 13 billion euros in renewable energies in 2021. The peak value for this in 2010 was around 28 billion euros. |

2.2 The Armed Forces Special Assets Act

Key contents of the law

In the Act on the Establishment of a „Special Fund of the German Armed Forces“ (BwFinSVermG)7https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bwfinsvermg/BwFinSVermG.pdf BwFinSVermG: The original designation was BwSVermG., §1 states that „on a multi-year average of a maximum of five years, 2 percent of the gross domestic product shall be made available for defense expenditures in accordance with NATO criteria“ on the basis of the current government forecast.

Note in this regard: If GDP declines due to economic recession, this automatically increases defense spending shares.

Drawn credits must be „repaid within a reasonable period of time“ no later than Jan. 1, 2031.

It should also be noted that several items in the current 2022 federal budget are designated as special funds. For example, the Energy and Climate Fund has been increased to EUR 106 billion. However, this special fund is also shown with a revenue side, primarily from national and EU emissions trading and CO2 pricing, respectively.8https://www.bundestag.de/presse/hib/kurzmeldungen-885902 The decisive factor for the designation as a special fund in this case is the management by several ministries.9See also the criticism of the environmental associations formulated in a joint open letter to Chancellor Olaf Scholz dated 29.3.2022: „Energy sovereignty through the largest climate protection investment package ever“. Source: https://www.bund.net/fileadmin/user_upload_bund/publikationen/bund/BUND_offener_Brief_Energiesouveraenitaet_Scholz.pdf

In contrast, the BwFinSVermG is expenditure that until now has apparently been completely covered by Section 14 of the federal budget. This effectively creates a shadow budget with a non-transparent „shunting yard“.

The 2022 economic plan of the BwFinSVermG shows 82 billion euros for future years. This amount is supplemented by items that have already been decided and previously booked in the „normal“ defence budget, which are now to be shifted to the special fund, thus pretty much exhausting the budget.10More details by Jürgen Wagner at: https://www.imi-online.de/2022/10/14/das-bundeswehr-sondervermoegen-ein-fall-fuer-den-rechnungshof/.

On the term of the BwFinSVermG, here are some comments from a technical paper:

How long the special assets will be used can only be estimated once all projects have been contracted and the schedules for delivery and thus the dates for invoicing are known. For the heavy-lift transport helicopters, for example, the delivery times extend over eleven years after the contract is signed, and for the U-212 CD submarines until 2034. FCAS and MGCS will perhaps only enter production at that time. This results in a duration of the special fund of at least eleven years with an average outflow of funds of 9 billion euros per year. Since some projects will have shorter durations, an outflow of funds of around 15 billion euros can be expected in the middle of the scope of the BwSVerm during some years.11https://esut.de/2022/06/meldungen/34634/ausschuesse-segnen-wirtschaftsplan-zum-sondervermoegen-ab/

Expenditure blocks by „dimensions

The investments planned with the BwFinSVermG are broken down in such a way that the compilation is not according to the branches of the Army, Air Force and Navy, but according to „dimensions“12See: https://www.bundeswehr.de/de/organisation.

The project list or economic plan (excerpts in Annex A.1) is to be updated annually, whereby each project over 25 million euros must be approved again separately in the Defence and Budget Committee. The projects are distributed across the „dimensions“ as follows:

Air (33.4 billion euros): including procurement of the F-35 fighter jet (see project example chapter 6.1) and CH-47F transport helicopter in the USA, as well as upgrading the Eurofighter for electronic warfare. With the transfer of existing items from Epl 14, this sum increases to 40.9 billion euros.

Command and control capability/digitalisation (20.7 billion euros): Radio communication according to international standards, especially for foreign missions.

Land (16.6 billion euros): Retrofitting of the Puma infantry fighting vehicle (see project example chapter 6.2) and successors for existing tank systems.

Sea (8.8 billion euros): among others, for the K130 corvettes and F126 frigates already in the realisation phase (see project example chapter 6.3), as well as the 212 CD submarine currently under development. With the transfer of existing items from Epl 14, this sum increases to 19.3 billion euros.

The economic plan also mentions 2.0 billion euros for personal equipment as well as research and development for the use of artificial intelligence for 422 million euros.

The digitalisation block, which is to lead to a complex networking of ground and air forces with a large number of individual projects, as exemplified in Chapter 6.4 with the FCAS/MGCS project, requires special consideration.

2.3 Foreign policy and industrial strategies

Specifications for the Bundeswehr

So-called white papers of the BMVg form the basis for the tasks of the Bundeswehr13The latter is currently specified in more detail in a separate document entitled „Conception of the Bundeswehr“, which was published in 2018.. These are addressed to both the Bundestag and the public. Still valid for the Bundeswehr is the White Paper of July 201614https://www.bmvg.de/de/themen/dossiers/weissbuch, which was announced as early as October 2014 and developed in an intensive discussion process.15The previous edition dates from 2006, with a content focus on justifications for foreign missions, against the backdrop of globalisation and Germany’s resulting economic interests and dependencies.

The current White Paper 2016 bears the subtitle „on security policy and the future of the Bundeswehr“. According to the White Paper, the main task of the Bundeswehr is once again seen in national and alliance defence, as a reaction to the Ukraine crisis since 2014. The suspension of compulsory military service, which has taken place in the meantime, is also indirectly addressed in the White Paper by referring to an increasing need for specialists such as IT experts, engineers and medical personnel.

The 2016 White Paper states with regard to arms expenditure:

The reorientation of the armament sector is based on the following premises:

– The Bundeswehr procures according to requirements and thus practices modern arms management.

– An independent, efficient and competitive defence industry in Europe, including the national availability of key technologies, is indispensable.

– Multinational cooperation is strengthened by the lead nation approach.

– Innovation is the key to securing the future.

– Transparency internally and externally has the rank of a strategic principle

Also noteworthy is the following reference, which is discussed in more detail in Appendix A.4:

„IT, with its typically short innovation cycles, needs to be procured faster than other equipment; and urgent needs for operations need to be further realised in a much more pragmatic way than the long-term planning of major weapon systems.“

The BwFinSVermG was also explicitly based on the 2016 White Paper as justification. However, the sum of 100 billion euros for procurement measures was decided without a parliamentary and societal debate on the benefits and deployment scenarios for the envisaged projects.16Sources from the Bundestag point out that the „special assets“ were already being discussed internally in October 2021. However, these are considered classified information. Currently, a new national security strategy is in the works.17A new national security strategy could lead to a new white paper for the Bundeswehr.

Industrial Policy and National Key Technologies

As already quoted from the 2016 White Paper, national key technologies play an essential role in the political requirements for the Bundeswehr.

Here, it is not the BMVg but the Ministry of Economics (BMWK) that plays a leading role. The BMWK has also been at the forefront of drafting the Federal Government’s strategy papers „on strengthening the defence industry in Germany“.

Following a paper published in July 2015, a new version was already published in February 2020. In contrast to the predecessor paper, not only are the commonalities between the civil security and defence industries emphasised, but reference is made above all to new technologies, such as digitalisation, artificial intelligence, unmanned systems, hypersonic technology, biotechnologies and cyber instruments.

Just as in the previous paper, the naming of key defence industrial technologies18https://www.bmvg.de/de/aktuelles/ruestung-liste-nationaler-schluesseltechnologien-ueberarbeitet-171464 plays a central role, with each of these being distributed in a graphic representation on three levels:

- National key technologies;

- European: Securing the technology, cooperation with European partners;

- Global: Recourse to globally available technologies.

| Fig. 2-3: Key military technologies The diagram is based on a graphic from the above-mentioned strategy paper of the BMWK (or BMWi). It is striking that most technologies are classified as „national“, although there is now a pronounced cooperation at the EU level in defence projects. Explanations: NBC defence: against nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. Airborne/air defence: e.g. Eurodrone Rotary and fixed-wing aircraft: currently via BwFinSVermG economic plan with F-35 fighter jet and CH-47F heavy transport helicopter. |

Arms production and exports

For armament projects, it can be assumed that 30 to 50% of the production is intended to cover the company’s own needs and that profit margins are mainly achieved through exports, which cannot be discussed in detail in this study.19It should only be pointed out at this point that the restrictions on arms exports that have been politically demanded in Germany for many years can easily be leveraged by the transnational corporate structures..

The official German arms export licences amounted to approx. 4 to 8 billion Euros in the last 10 years with strong annual fluctuations.20See also IMI 2022: Handbuch Rüstung

According to the economic plan for the BwFinSVermG, two projects from the USA (F-35 fighter jet and Chinook transport helicopter) in particular also include defence equipment to be imported. However, it must be taken into account that the desired delivery batches also include special features with industrial value creation in Germany. The cost volume of globally imported value added is therefore likely to have a share of significantly less than 20%.

Climate change as a military security risk

In the USA in particular, the military has been dealing with the consequences of climate change for many years. The main focus is on resilience in the face of the multiple effects of tropical cyclones. The Scientific Service (WD) of the German Bundestag has summarised this topic in two complementary documentations 202121Armed Forces and Climate Change [WD 2 – 3000 – 065/21 (Nov. 2021) and 202222Climate-related Challenges for the German Armed Forces [WD2 – 3000 – 014/22 (March 2022). Among the numerous sources listed, the World Climate and Security Report 2020 23This is published by the International Military Council on Climate and Security, – https://imccs.org/ is cited, where, among other things, water insecurity as well as the threat to military infrastructure, equipment, operational readiness and missions are mentioned. The WD’s supplementary documentation of March 2022 states in the introduction:

The Bundeswehr will intensify the already initiated reduction of its environmentally harmful footprint to a minimum.

The WD document also explicitly notes that the Bundeswehr must participate in efforts to reduce emissions, but that it can only use low-emission and green technologies to a limited extent, especially in the context of foreign missions.24See also Chap. 5 of this study on the consequences of the German Climate Protection Act as well as Chap. 7.1 Problem Outline Climate Change..

2.4 Civilian benefits of armaments

The costs incurred for armaments and the resulting environmental impacts must of course be offset by the civilian benefits, insofar as these can be represented. A corresponding analysis, however, yields a very poor balance, not only for the use of human resources, but also for armament objects in civilian disaster relief operations.25See Peil u. Brandt, 20220: Sections 2.3 and 2.4 Civil-military cooperation.

An example of this are transport helicopters, whose inventory in the Bundeswehr considerably exceeds that for civilian use (717 in 2021)26https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/155527/umfrage/anzahl-der-hubschrauber-in-deutschland/. However, the use of Bundeswehr helicopters for fighting forest fires with fire-fighting water tanks has shown that they are only partially suitable for this purpose, as stated in a report by the Ministry of the Interior of the State of Brandenburg as an analysis of the forest fires in 2018.27Former link (no longer accessible): https://mik.brandenburg.de/media_fast/4055/Waldbrandbericht_2018.pdf

The procurement of the US CH-471 transport helicopter envisaged via the investment package is unlikely to change this, as it is primarily designed for the air transport of heavy military land vehicles.28https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/ch-47f-block-ii.htm

However, activities to combat forest fires in the future are taking place at EU level for the use of firefighting aircraft. Airbus, together with the Spanish Air Force, the European fire protection authorities and the Spanish Ministry of Ecological Change and Demography, has developed and tested a fire extinguishing system for the A400M transport aircraft. According to Airbus, the fire extinguishing equipment can be used without design modifications by means of a simple conversion.29https://esut.de/2022/07/meldungen/35620/a400m-auf-dem-weg-zum-feuerloeschflugzeug/

In this context, it is also relevant that the personnel and equipment of the THW as a civilian institution of the Federal Government for disaster situations are very modest compared to the Bundeswehr (see Annex A.3 – Tab. A-2: Total vehicle stock of the Bundeswehr and comparative figures).

2.5 Conclusions

The following points of criticism thus arise with regard to the military build-up with the investment package:

No planning for real security risks: There is still no project-oriented planning in the most important institutional area of federal expenditure against the global security risk of climate change and the necessary resilience against hurricanes, floods and forest fires. The civilian benefit of the arms investments is thus minimal.

Intransparency and inefficiency of the entire procurement process chain: There are numerous reports on this, especially from the BRH.

Unrealistic industrial strategy with key military technologies: The German defence industry receives a boost with the investment package, which shows that its promotion is primarily not due to lobbying (which undoubtedly also exists), but to political-strategic guidelines. This shows parallels with the development of the civilian nuclear industry in Germany from the mid-1950s onwards.30To simplify matters, reference can be made to the biography of Franz-Josef Strauß and his activities as nuclear minister from 1955 to 1956. See: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Josef_Strau%C3%9F However, this concept is questionable, especially against the background of the extreme increase in raw material prices.

Prioritisation at the expense of the expansion of renewable energies: The investment package for the German Armed Forces leads to direct and indirect repercussions in the expansion of renewable energies31For more details, see also chapter 4 on the direct competition of metallic resources for renewable energies versus defence investments. and public services of general interest.

References

IMI, 2022

Handbuch Rüstung | Hrsg. Informationsstelle Militarisierung e.V.

http://www.imi-online.de/2019/11/20/nachhaltige-bundeswehr/

Peil, Karl-Heinz; Brandt, Götz. 2020

Militär und sozial-ökologische Konversion | Hrsg: Ökologische Plattform bei der Partei DIE LINKE

https://umwelt-militaer.org/militaer-und-sozial-oekologische-konversion/

Wagner, Jürgen. 2022

Im Rüstungswahn – Deutschlands Zeitenwende zu Aufrüstung und Militarisierung

PapyRossa-Verlag, Oktober 2022